If You Knew Lorca*

*🪕 If you knew Lorca, like I know Lorca … 🎶

(then you’d know only a little about this wonderful poet,

but be eager to know more).

Viaje a la Luna

Federico García Lorca

Wattis Institute for Contemporary Arts

(Museum for California College of the Arts)

Ongoing – October 11

The Exhibition

Viaje a la luna (A trip to the Moon) is inspired by the only movie script written by the renowned Spanish poet, playwright and artist Federico García Lorca. Featuring both national and international artists, this exhibition builds upon themes explored in the script, as well as the social and political context of its creation in the late 1920s. The artworks draw parallels to the present, the 2020s, with politically far-right nationalist movements and fascist ideologies once again on the rise, causing the world to become more insular and uncertain.

Lorca wrote the script in New York in 1929 after a series of conversations with the Mexican artist Emilio Amero. Production began in Mexico City in 1932, with a crew that included notable Mexican artists of the time, such as Lola Álvarez Bravo and her husband, Manuel Álvarez Bravo. However, filming was halted after Lorca’s murder by the Spanish Nationalist army in 1936. The project faded into obscurity, becoming another unfinished work and enigma in history.

Viaje a la luna speculates on what the film might have been, establishing a dialogue between a group of contemporary artists and the fragments of Lorca’s life and screenplay. For Lorca, art was both a refuge and a means to forge an identity, expressing his politics and his deeply personal, often distressed search for love—an indirect reflection of his homosexuality. Through historical and contemporary artworks, the exhibition revolves around the question: What would the film have been like?

The exhibition will travel to the Centro Federico García Lorca in Granada, Spain on October 30.

Lorca

Federico García Lorca was born in 1898 in Fuente Vaqueros, Granada, in Spain. In his short life (assassinated, age 38), he published thirteen major works of poetry and theater that centered Andalusian culture and Spanish folklore through an avant-garde lens. A homosexual poet and playwright who focused on the stories of marginalized figures and communities, Lorca’s work – perceived as left-leaning and socialist – was provocative in conservative right-wing circles. Through themes of passion, repression, and death, he investigated gypsy culture, the plight of rural workers, and the repression of women in Spanish society.

In June 1929, aboard the Olympia (sister ship of the Titanic), Lorca arrived in New York City to study for a year at Columbia University. After experiencing heartbreak from a passionate relationship with the artist Emilio Aladrén, and grappling with the success of his 1928 poetry collection Romancero Gitano (Gypsy Ballads), Lorca found himself at a creative and emotional crossroads.

In New York, Lorca set out to find a new voice. Confronted by the infinite skyscrapers and bustling streets, he soon encountered the rich art scene of the Harlem Renaissance, via his friendship with the writer Nella Larsen. Finding affinities between the social discrimination of the Romani in Spain and African Americans in the US, Lorca would write to his parents about the insatiable appetite of American capitalism and its stark class disparities.

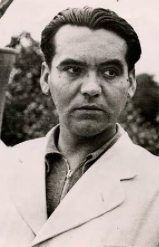

Lorca in NYC, age 31

Lorca stayed in NYC for a mere nine months as he studied English at Columbia University. Yet, he was profoundly affected by the experience. He lived in Manhattan during the 1929 Stock Market Crash. His experiences with urban alienation, racial prejudice, and the commercialism of American capitalism culminated in an influential collection of experimental poetry, Poet in New York, published posthumously in 1940. Still, it wasn’t all grim. H found comfort in his visits to Harlem, finding spiritual purity in its thriving jazz and gay culture.

The political climate of the 1920s in the U.S. was marked by conservative, nationalist politics. The exhibition makes connections between the political climate of the US in 1920s and 2020s.

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917 and the Great War (World War I), the country experienced a surge in anti-communist and anti-socialist sentiment. Meanwhile, in Spain, the dictatorship of Miguel Primo de Rivera had been established in 1923, and the country was economically reeling from the Rif War with the Berber tribes in Morocco. It was in the heart of this North American metropolis that Lorca connected with intellectuals and artists from the Spanish and Latin American left, such as Fernando de los Ríos, José Vasconcelos, María Antonieta Rivas Mercado and Emilio Amero.

A cinephile, Lorca was introduced to Amero’s film work by Rivas Mercado. Amero’s most recent piece at the time, 777 [now lost] is described as an abstract film, featuring superimposed images of machines and mechanical gears common in assembly-line manufacturing. Amero’s interest in cinema, the most modern medium of the time, made film an ideal tool to explore the conditions of contemporary life and the increasing impact of technology. Impressed, Lorca befriended him and wrote a film script for Amero to direct.

I don’t know much about graphology, but I think it takes a strong sense of self to write the initial capitals of your name in letters so large.

Viaje a la luna (1929)

Written over two days in Amero’s apartment, Viaje a la luna was conceived as a silent film composed of 72 loosely connected sequences. Entirely visual in its form, the film presents the city as an abstract inner landscape, filtered through Lorca’s surrealist imagination. Using mystical, romantic, and coded imagery of violence, Lorca evokes themes of societal repression and personal persecution. Renowned Lorca scholar, Ian Gibson, notes that the script “does not describe a journey to the moon, but rather a symbolic voyage toward death in search of unattainable love. From the haunting opening sequence—‘from the white bed against a grey wall, where the numbers 13 and 22 emerge from the sheets in pairs until they cover the bed like ants’—to the final image of the moon and wind-blown trees, the film unfolds like a dreamscape.”

In quiet 1940 photographs taken by Amero, a pair of yoked oxen evoke a fading rural way of life. Taken a few years after Viaje a la luna would have been produced, Amero’s photos offer a glimpse into what the film could have looked like. They capture a world at the threshold of change, where the oxen become stand-ins for figures caught in the crossroads of modernization.

Read alongside his New York poems, Viaje a la luna becomes a deeply personal narrative of Lorca’s anxieties. This is especially evident in sequence 36 – “Double exposure of iron bars passing over a drawing, The Death of Saint Radegunda” – which resembles two of Lorca’s drawings from the same period, both featured in the exhibition. In each artwork, the dying figure resembles the poet himself, lying on a table with several wounds. One of these drawings, dated “New York, 1929,” bears the same title as the film sequence and captures the symbolic violence and vulnerability at the heart of Lorca’s vision.

Soon after completing the script, Lorca departed for Havana, Cuba, and Buenos Aires, Argentina, before returning to Spain, in 1930. He founded a traveling theatre company, La Barraca, which brought plays to rural villages, promoting Spanish culture and accessibility. He also wrote his famous Rural Trilogy during this period.

The project Viaje a la luna would not be completed.

While Viaje a la luna was never completed, in a strange twist of fate, Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times was released in 1936, the year that Lorca was murdered. These two artists were prominent contemporaries who explored similar themes of humanity struggling against oppressive modern forces. Both used their art to critique social and economic injustices during a period of rising fascism and rapid industrialization in the 1930s.

Lorca’s Assassination

On August 16, 1936, at the age of 38, Federico García Lorca – the most renowned Spanish poet of his time – was kidnapped by anti-Republican fascist rebels and executed sometime between 2 a.m. and 3:30 a.m. A police report from the incident states, he was killed for being a “freemason belonging to the Alhambra lodge” and someone who partook in “homosexual and abnormal practice.”

Lorca did not die alone. It is believed that Lorca, along with others, was buried in an unmarked mass grave between the towns of Alfacar and Víznar, about seven miles from his home in Huerta de San Vicente. The site is now a park that honors those killed and disappeared during the Spanish Civil War. A commemorative plaque there reads, “LORCA ERAN TODOS.” (All were Lorca) Lorca eran todos is also the title of a 2008 theater-documentary directed by Pepe Rubianes, which serves as a tribute to the Spanish poet Federico García Lorca and all the democrats executed during the Spanish Civil War.

Lorca’s Sexual Identity

No account of Lorca or evaluation of his works is complete without an acknowledgement of his homosexuality. It is the knife’s edge of pain that whispers through his works. No one can hide who he is all the time. An artist can never hide who he is, at least not from himself. [I use “he” and not s/he/they here because my comments refer specifically to Lorca.]

Lorca worked closely with Salvador Dali, the Spanish surrealist artist, and the two became long-time friends. It was rumored that their friendship went further and they exchanged letters throughout Lorca’s life. It’s not clear that Dali and Lorca ever consummated their relationship. Dalí had a notorious aversion to physical contact in general and feelings of great sexual inadequacy. His anxieties and fears often resulted in impotence. (While Dali was married to his muse, Gala, for most of his life, most biographers believe that they never had sexual contact.)

Dali & Lorca

For more than five decades his family denied his sexual identity. Lorca's family denied researchers access to his archives if they wanted to explore his sexuality. Lorca’s sexuality was hidden because no one wanted to admit that Spain’s greatest poet was gay, despite the notes from the police report of his death. A tightly held secret during Generalissimo Franco’s regime, acknowledgement of Lorca as a gay man finally happened a decade years after Franco’s death.

His homosexuality was slowly revealed through posthumous publications of his work and the research of his primary biographer, Ian Gibson.

His homoerotic play, El Público (The Audience) was censored for 40 years. The first version of his Sonnets of Dark Love was censored to remove any allusions to homosexuality. The complete, uncensored version of Sonnets of Dark Love was published in the mid-1980s, revealing its true queer content.

In 1989, (53 years after Lorca’s murder) Ian Gibson, broke decades of silence and censorship by Lorca's family and Spain's literary establishment. He revealed extensive evidence of the poet's homosexuality in his book Federico García Lorca: A Life. Finally, in 2010, the identity of Lorca's last lover, Juan Ramírez de Lucas, was confirmed by mementos and letters he left for his sister, further solidifying the biographical record.

VIl

Ghazal of Dark Death

I want to sleep the sleep of apples,

far away from the uproar of cemeteries.

I want to sleep the sleep of that child

who wanted to cut his heart out on the sea.

I don't want to hear that the dead lose no blood.

that the decomposed mouth is still begging for water.

I don't want to find out about grass-given martyrdoms,

or the snake-mouthed moon that works before dawn.

I want to sleep just a moment,

a moment, a minute, a century.

But let it be known that I have not died:

that there is a stable of gold in my lips,

that I am the West Wind's little friend.

that I am the enormous shadow of my tears.

Wrap me at dawn in a veil,

for she will hurl fistfuls of ants:

sprinkle my shoes with hard water

so her scorpion's sting will slide off.

Because I want to sleep the sleep of apples

and learn a lament that will cleanse me of earth;

because I want to live with that dark child

who wanted to cut his heart out on the sea.

Lorca, shortly before his death

For more information about the Wattis Institute of Contemporary Arts and the Lorca exhibition, click here.

Gallery hours for the Public:

Wednesday – Saturday, Noon–6pm

Closed Sunday, Monday, and Tuesday

Wattis is FREE

Location:

145 Hooper Street

Level 2

San Francisco, CA 94107